While serving overseas, Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) personnel have communicated with home through a variety of ways. Letters were by far the most common during the two World Wars and provide us with an insight into New Zealand families separated by war.

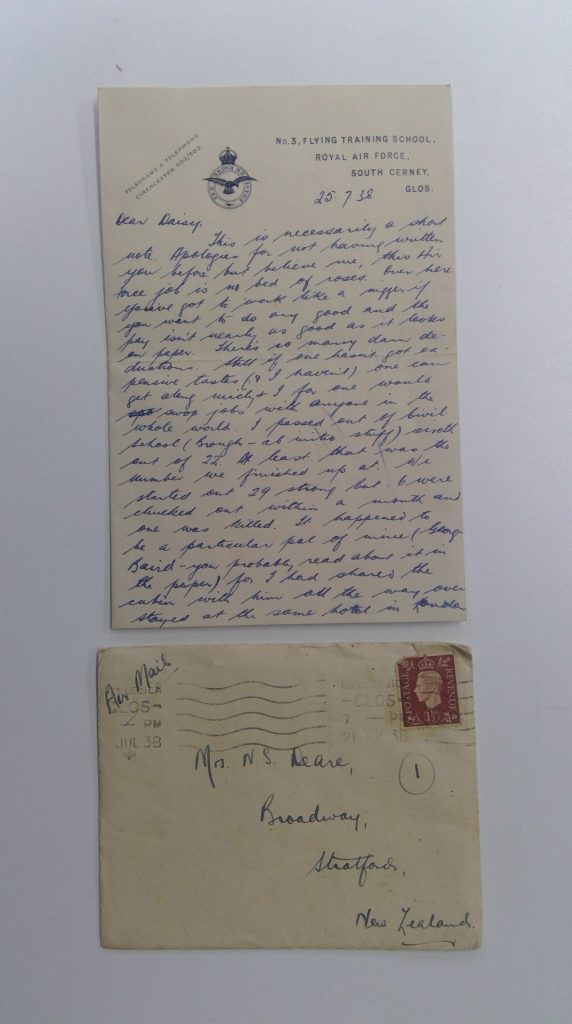

As we commemorate Anzac Day, we can look at one collection of such letters kindly donated together with log book and photographs last year. They were written by Herbert (known as George) Blackmore from England and the Middle East to his sister Daisy and her husband Norris in Stratford, New Zealand. Despite the presence of censorship, George was able say quite a bit about what he was experiencing, offering us an insight into the experiences of war.

Herbert George Percy Blackmore was born in Wellington on 15 March 1914 to Herbert and Minnie Swinfield Blackmore. After the family moved to New Plymouth, he attended New Plymouth Boys’ High School and later worked as an estates clerk for the Public Trust Fund in New Plymouth. With the expansion of the Air Force after 1937, George applied and was accepted for a Short Service Commission in the Royal Air Force (RAF) which entailed going to England to train as a pilot. With limited facilities in New Zealand at the time and war clouds looming, this was the best way to train many pilots from New Zealand quickly, using British resources.

After a long sea voyage, George and other New Zealanders arrived in England on 10 May 1938. After a stay in London, the New Zealanders reported to the aerodrome at Brough in Yorkshire. This belonged to the Blackburn Aircraft Company and was home to No. 4 Elementary and Reserve Training School. While it was an RAF unit, the instructors and the staff worked for Blackburn. Here he began his pilot training but within a month, on 16 June 1938, an accident occurred and a pilot was killed, as he told Daisy in a letter:

“It happened to be a particular pal of mine. (George Baird – you probably read about it in the paper) for I had shared the cabin with him all the way over, stayed in the same hotel in London and finally had the same instructor….You see I’d been doing a circuit about a hundred feet above him and say a couple of hundred yards behind when he started to spin so you see I had a grandstand seat”.

Shaken by what he had seen, he and the other remaining New Zealander on the course, Joe Berry went out until the early hours and got very drunk. They were still drunk the next morning and were subsequently grounded but common sense prevailed when their instructor realised how witnessing Baird’s death had clearly affected them.

In July 1938, now commissioned as a Pilot Officer, George was posted to No. 3 Flying Training School at South Cerney, near Cirencester. Here he completed his training and received his pilot’s badge in October 1938. In January 1939, he wrote to Daisy:

“Now I really have some news. On 4 March I am to have a month’s leave then sail for Iraq. Expect to go to Habbaniya, 60 miles west of Baghdad, where one is supposed to do nothing but fly and play games”.

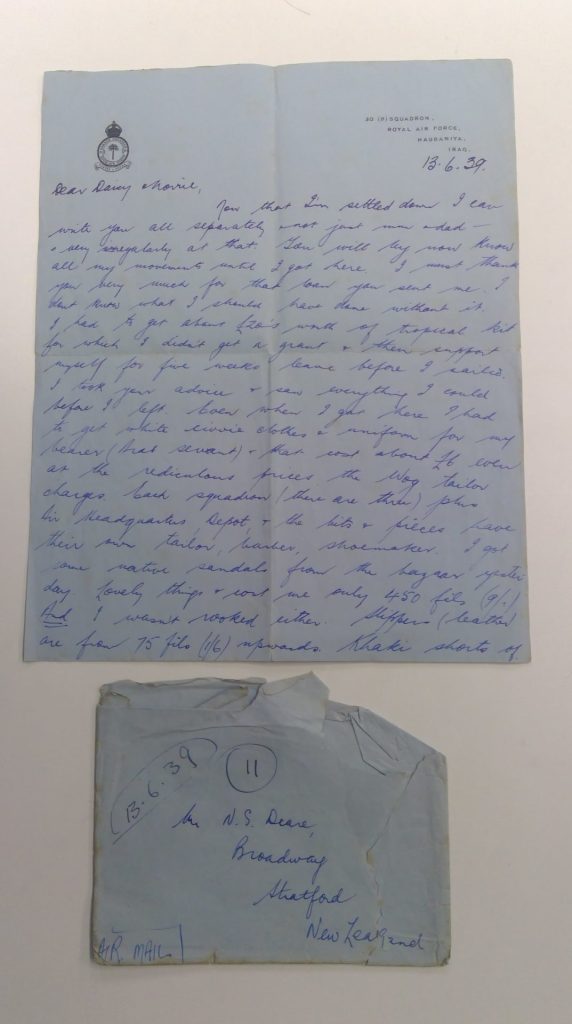

Clearly the impression he had of the RAF in the Middle East was a peacetime one, with little for them to do except watch for unrest if it occurred amongst the local population. On arrival, it was confirmed. He was posted to No. 30 Squadron flying Bristol Blenheim bombers (and later, some of the fighter variant). This unit had been serving in India and the Middle East since the First World War and here he would be introduced to the British colonial way of service life.

His first letter home on 13 June 1939 described all the tropical kit he had to purchase for himself and his bearer (servant), their cost, and the fact that despite the daytime heat, “in winter it can get just as cold as Taranaki”.

By August 1939, George had settled into the routine of a Middle East squadron in peacetime and was keenly hoping to visit other places, such as Egypt, Cyprus and Palestine. With the outbreak of war with Germany on 3 September 1939, however, the situation changed and worsened further when Mussolini brought Italy into the war in June 1940. By this time the Squadron was in Ismailia in Egypt and confronted the Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica) in the initial exchanges in the Western Desert.

George wrote to Daisy on 21 January 1940, informing her he had something to remind him of home that had been sent to him:

“The coloured picture of Mount Egmont now adorns the wall of our Flight Office, much to the disgust of the Flight Commander who’s a Canadian”.

He also wanted to know all about the newly opened station back home at RNZAF Bell Block at New Plymouth.

No. 30 Squadron was sent to Greece in late 1940 to defend against the Italian invasion from Albania. Here, George encountered first-hand the risks of combat flying. In a letter to Daisy written on Christmas Eve 1940, he told of a narrow escape earlier that month, after crash-landing on Corfu:

“It seems that this Christmas will be much quieter than last. You see I’m spending it in hospital. No, I haven’t been wounded but am merely in for observation. About a fortnight ago, I popped over the lines to do a bit of ground strafing… and as I got shot up a bit I had to land miles and miles from anywhere. I wasn’t hurt at all but it took me nearly a week to get back to any civilization again. However, I lived well enough on the hospitality of the Greek peasants who are absolutely flat out to do anything for the British. However, on the first day of the trip home some damn fool of a driver drove straight into a bomb-crater. Result, he got a broken nose, my gunner got concussion and I got a cut on the top of my head”.

Seeing the realities of war on the ground and for civilians also spurred his recovery, as he continued:

“Still, I’m all for having another crack at them as soon as possible, I suppose it was worth it as I’ve really got to hate the Italians. I’ve seen some of their work on civilians and didn’t like it a bit. I really enjoyed seeing troops scatter and crumple as I opened up with my guns. Still enough of that. I suppose quite a lot of us feel like that”.

After a month of sick leave, George was posted to another Blenheim unit, No. 55 Squadron in Egypt and found himself once again in the thick of the fighting for North Africa. On 28 April 1941, he described another encounter with the Italians over the Axis airfield at Derna on 17 April 1941, accompanied by fellow New Zealander, observer Sergeant William Cole of Wellington and British air-gunner Sergeant Briggs:

“I think you would be interested to know that my gunner will probably be recommended for the D.F.M. [Distinguished Flying Medal] A few days ago, we were bombing an enemy aerodrome when a fighter appeared. I was all on my own, so when I had dropped my bombs I set sail for a nice big cloud not far away. Then the fighter came in and on his first burst sounded the gunner in the left hand and in the same arm above the elbow. In spite of this, he cleared a stoppage in his gun and when the Ity came in again he let him have it good and hard. The Ity didn’t try it again, so I think he must have been hit somewhere or other or just thought better of it. Anyway, it took another two hours to get home and all that time the gunner never said a word about his wounds. I didn’t know he had been wounded until I landed… By the way, the aeroplane had 23 holes in it. How’s that for the luck of the twirps? Don’t tell mum, she wouldn’t see the funny side of it.”

George was a veteran member of the Squadron by August 1941 and nowa Squadron Leader, but the even with the experience of 32 missions, by October 1941, his luck was running out.

On 20 October 1941, he and Sergeant Cole, together with Australian air-gunner Sergeant Leslie Rhodes were leading a formation of three Blenheims attacking the airfield at Gambut in Libya. This time it was the Germans who were waiting. Four Bf 109 fighters attacked as they turned for home and George’s aircraft must have been hit. It slowly lost height before plunging into the sea 30 miles north of Gambut. George and his Anzac crew were never found and are commemorated on the El Alamein Memorial in Egypt. As New Zealanders, George and William Cole are also remembered on our own Roll of Honour here at the Air Force Museum of New Zealand.

Ka maumahara tonu tātou ki a rātou.

We will remember them.