Archives Technician Louisa Hormann recently presented at the Wings Over New Zealand Forum Meet at the Air Force Museum of New Zealand. She spoke about the Guinea Pig Club and the innovative care administered to its members by New Zealand pioneering plastic surgeon Sir Archibald McIndoe. This blog explores some of the connections this international band of brothers has with Aotearoa New Zealand.

CONTENT WARNING: This blog contains images of severe burns.

The Guinea Pig Club was formed in 1941 by and for RAF and Allied aircrew undergoing gruelling burns surgery at Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, England. Not all RAF casualties were treated at East Grinstead, but all members of the club were treated by the pioneering New Zealand plastic surgeon, Archibald McIndoe.

By the end of World War One, plastic and reconstructive surgery had become the main branch of military surgery but was still very much a developing area of medical science. The name “Guinea Pig” referred to the experimental nature of the airmen’s treatments. McIndoe’s older cousin, Sir Harold Delft Gillies, was a renowned World War One plastic surgeon, and it was under his tutelage that McIndoe trained to meet the particular challenges of the next world war – in this case, faces (and other areas of the body) that had been severely burned.

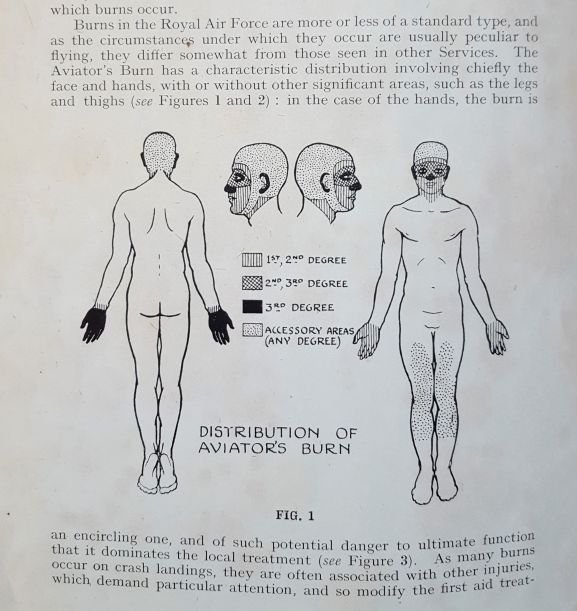

Air Ministry Pamphlet for the First Aid and Early Treatment of Burns in the Royal Air Force (1944; 1956, first and second editions). From the collection of the Air Force Museum of New Zealand.

Many of the club’s early members were fighter pilots, but later on the majority came from Bomber Command. As burns cases increased, the Air Ministry published this pamphlet on First Aid and Early Treatment of Burns in the Royal Air Force, to educate RAF medical officers, who were usually first on the scene of such accidents. Why were aircrew so badly burned? And why were their hands and faces most at risk? This diagram in the first edition pamphlet clearly shows and explains the distribution of aviator’s burn.

These airmen didn’t just suffer physically from their ordeal, but they also suffered psychologically. It was thanks to McIndoe’s surgical work and his social work, that these men eventually continued their lives in employment and most importantly, in good spirits. The club’s strong camaraderie and social life, with the advocacy provided by its own members and benefactors – and especially by McIndoe – gave the airmen new confidence in life. The club ensured their social inclusion in the wider community, and by war’s end, it had 649 members. The majority of Guinea Pigs were British, but also included New Zealand, Australian, Canadian, American, French, Czech, Polish, Belgian, Russian, and Turkish members. There were over 170 international “Guinea Pigs”, making up more than a quarter of the club’s total membership.

Sir Archibald McIndoe

Archibald McIndoe, and his fellow Otago University contemporary Rainsford Mowlem, represented the next generation of plastic and maxillofacial surgeons, following the example laid by Gillies and Henry Percy Pickerill in the First World War. Together, these four men were considered the “Big Four” – the only four fully experienced plastic surgeons working in the UK at the outbreak of the Second World War. All four had connections to New Zealand: all except Pickerill were born in New Zealand, with Pickerill permanently emigrating to New Zealand in his late twenties. Gillies and McIndoe were born in Dunedin, and McIndoe and Mowlem both educated at Otago University. [1]

McIndoe’s surgical team first formed at his Harley Street practice in London, 1935. Known as “The Immortal Trio” or the “Firm of Three”, they included McIndoe, Anaesthetist John Hunter (known as the “Pass-out King”) and Theatre Sister Jill Mullins. McIndoe was appointed the RAF’s consultant in plastic surgery in 1938 and, together with Canadian plastic surgeon Group Captain A Ross Tilley OBE RCAF, developed ground-breaking techniques for reconstructing and rehabilitating burns survivors.

As well as physically reconstructing his “Guinea Pigs”, McIndoe helped their reintegration into society by working with local families to accept patients into their homes as guests. This was especially welcome as many international patients could never have family and friends visit during their hospitalisation. But it also contributed to the positive social reintegration of the airmen in the local community, and to East Grinstead becoming known as ‘the town that never stared’.

The following New Zealand airmen, both Wireless Operator-Air Gunners serving with RAF squadrons, were treated by McIndoe during the war.

Vernon Mitchell

Although entitled to membership of the Guinea Pig Club, Flying Officer Vernon E. Mitchell never joined. [2] Mitchell was serving as a Wireless Operator-Air Gunner with No. 3030 Ferry Training Unit at Talbenny, South Wales, waiting for deployment to the Middle East, when on the way back to Wales on 10 April 1943, his Wellington bomber crashed and exploded on approaching Talbenny. We don’t have Vernon’s diary in the collection, but here is an excerpt published in the Sunday Star Times:

‘I had a picture of mum receiving the cable & it was up to me to say whether it would be injuries or otherwise, so I went to it. I didn’t remember any more until I found myself in a flying dive & with the release catch in my hand. The astro hatch swung open, I had a vague recollection of other figures around me. Then I found myself on the ground, & what a relief. It all happened in seconds, I looked down at my hands, the palms were bloody and the skin on the back was white and hung in shreds, the face felt very tight & the legs felt sticky … My thumb was hanging off at the top and my chin lips & nose had knocked against some hot metal.’ [3]

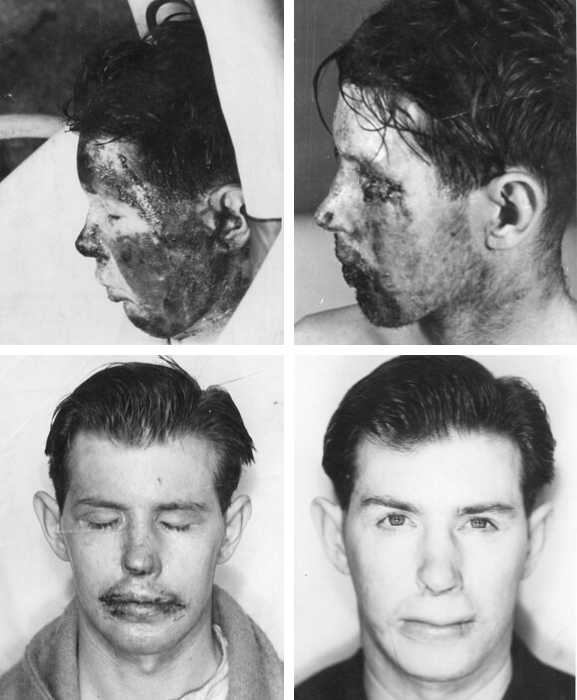

Vernon suffered severe burns to his face, arms and legs, and was treated at RAF Cosford’s burns ward in Shropshire, under McIndoe’s supervision. He remembers McIndoe visiting his ward three months into his recovery and scrawling on his body to outline the operations needed. Besides these photographs, we also have a copy of his official record of burns treatment in the archive. These are dated 11 April 1943-18 July 1945 and include assessment notes and recommendations from McIndoe. Vernon was back flying before the end of the war, though not in the combat role he had originally trained for, and right into his nineties, was still undergoing occasional surgery to deal with the lingering effects of his earlier operations.

Jack Williamson, DFC

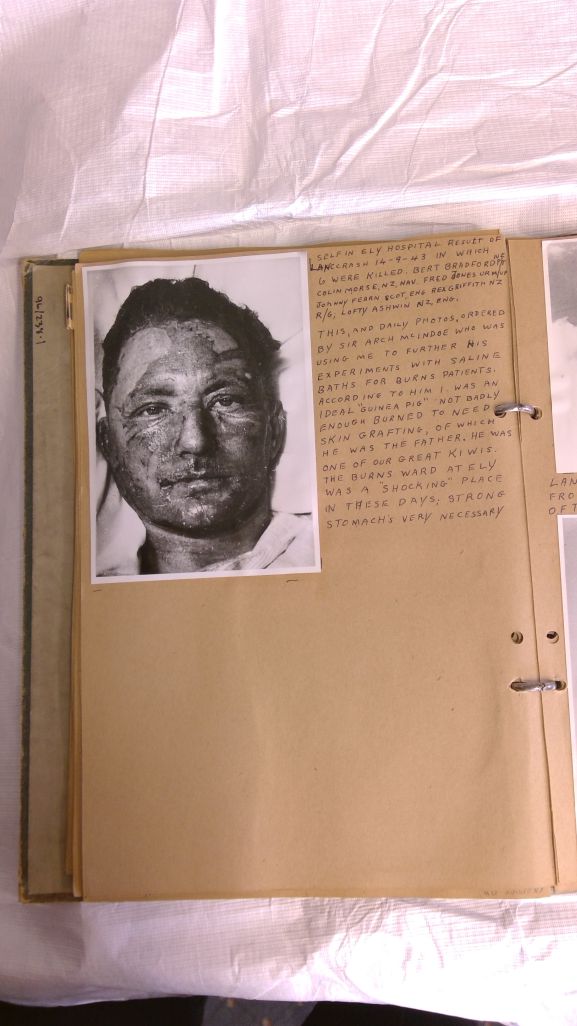

Another Kiwi Wireless Operator-Air Gunner, Flying Officer Ivan John “Jack” Williamson DFC, underwent surgical treatment for severe burns that year. He was flying with 115 Squadron RAF when on 14 September 1943, his Lancaster MkII crashed north of RAF Downham Market, after feathering two engines at 1,200ft during an air test. Six crew were killed, including three RNZAF airmen. Jack was one of two survivors, and described his experience in Scramble: Memories of the RAF in the Second World War, by Martin Bowman:

‘We had 1,500 gallons of high-octane fuel aboard. The fuel tanks exploded on impact and, lit by the engines, became a wall of flaming petrol. The aircraft broke its back just behind the second spar, flipped over the embankment and Sergeant Michael Read, the bomb aimer and myself were airborne for about 70 yards. We passed through the wall of petrol and became flaming torches, landing in a foot of mud, water and lots of bulrushes, where we burned quite furiously.’ [4]

The two survivors were found by an old carpenter who rolled them in the mud to put out their fires, and a Red Cross nurse who was waiting for her train nearby managed to administer injections from her emergency kit. From there, they were taken to Ely Hospital, where Jack was an in-patient for two months. He was treated by McIndoe and photographed every morning to record his early grafts. He was also treated to saline baths, a burns management technique introduced by McIndoe.

In 1939, standard first aid treatment for burns was coagulation therapy with tannic acid gel, which formed a hard crust, immobilising fingers and toes, making skin grafting difficult. McIndoe quickly abandoned this method in favour of introducing saline baths. Meikle describes the procedure as follows: ‘After the patient was lifted out of the bath the burned areas were cleansed, dusted with sulphonamide powder and covered with tulle gras dressings before skin grafting.’ [5] This significant change to the way burns were managed was vital to the ongoing success of the surgical treatment itself.

References

[1] Murray C. Meikle, Reconstructing Faces: The Art and Wartime Surgery of Gillies, Pickerill, McIndoe and Mowlem, Otago University Press (Dunedin, New Zealand) 2013, p.107

[2] Errol W. Martyn with Air Force Museum of New Zealand, Swift to the Sky: New Zealand’s Military Aviation History, Penguin (Auckland, New Zealand) 2010, p.153

[3] Vernon Mitchell, in “The patchwork man” by Adam Dudding, Sunday Star Times, 1 July 2012. http://www.stuff.co.nz/sunday-star-times/latest-edition/7199145/The-patchwork-man

[4] Jack Williamson, in Martin Bowman, Scramble: Memories of the RAF in the Second World War, Tempus Publishing Limited (Gloucestershire, England), 2006, p.129

[5] Meikle, Reconstructing Faces, p.129