In a previous blog we looked at how RNZAF personnel were sent to Japan in 1946 with ‘J-Force’, part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF). In a continuation of this 75th anniversary blog, we’ll take a look at what those RNZAF personnel did as part of J-Force and how it ended.

No. 14 Squadron in Iwakuni

Following their arrival in Japan in March 1946, No. 14 Squadron found themselves stationed at Iwakuni in southern Honshu. The airfield, like many others, had been heavily attacked during World War Two, with bomb craters still in the runway and bullet holes in the hangars. Once operational, the Squadron’s Corsair aircraft played a full part in monitoring the occupation of the former enemy’s home territory. They patrolled a large area, looking out for any sign of insurgency and for illicit fuel or weapons dumps. They also monitored things like schoolyards for banned military parades as Japanese culture was demilitarised by the Allies.

Smuggling from nearby Korea was also an issue and low level patrols over the sea were flown to deter vessels from attempting to land. They also co-operated with other air forces, sometimes taking the opportunity to dogfight with Royal Australian Air Force Mustangs.

During this time, No. 41 Squadron also played a vital role in maintaining supply and communication links with New Zealand for the units in Japan. The route was a 20,000km round trip and after a survey flight in February 1946, regular flights by Dakotas were undertaken weekly. They carried mail, spares and supplies for the New Zealand Army contingent. With long range fuel tanks, the Dakotas hopped across the Tasman Sea, then to Darwin, and then the Philippines, Okinawa and finally, Iwakuni. Bad weather was a constant threat, but the crews pressed on regardless, pushing themselves and their aircraft to the limit.

An unfamiliar culture

One of the main features of the experience of J-Force was the exposure of these New Zealanders to a strange and unfamiliar culture and one which until recently had been a bitter enemy. They were also surprised by how they were received. 14 Squadron pilot Bryan Cox recalled:

“Whenever we met a Japanese walking in the opposite direction, identified as such by the clip-clop of their wooden jandals, we would say ‘Konbawa’, meaning ‘Good Evening’, and without exception they would reply in a similar fashion”.

The officers also had house boys as servants. These youngsters were often studying as part of the process of democratisation and Cox also noted:

“…it was impossible not to be deeply impressed by their obvious nationalist diligence and terrific sense of humour. As we got to know them more deeply it seemed a complete enigma how they had proved to be such a ferocious enemy.”

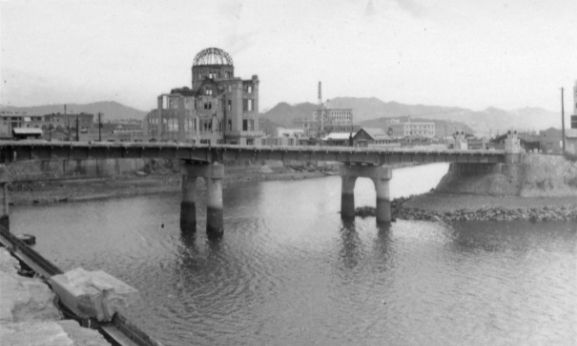

Time off was spent visiting tourist landmarks and shopping for souvenirs to send home. Visits to nearby Hiroshima were a weekend activity. Here they witnessed first-hand the effects of the atomic bomb on both city and people. Poverty was rife, and some of the metal sheets covering the hangars at Iwakuni were repurposed to provide makeshift shelters for the refugees. Sports, like baseball was another diversion for the men.

Other RNZAF contributions

As well as No. 14 and No. 41 Squadrons, a few individual RNZAF servicemen were sent to Japan on special duties. Flight Lieutenant Andrew Grimwood kept a diary of his attachment to the BCOF Headquarters in 1947-1948. During his time there, he witnessed one of the other purposes of the Occupation; the trial and conviction of Japanese leaders and war criminals by the War Crimes tribunal. On 10 May 1947, he visited the court:

“Once ensconced my first glance was for the men who were responsible for Pearl Harbour and all that followed! They were singularly calm and appeared to be in that state of mind which is often induced in spectators at involved legal proceedings… Could one expect them to be anything but bored? Particularly as the outcome is more or less a foregone conclusion. For many of them, death or life imprisonment.”

Time to come home

In February 1948, No. 14 Squadron moved to nearby Bofu, as the Occupation drew to an end. Later that year, in October, the Squadron’s veteran Corsairs, having reached the end of their service life, were piled up on the airfield and burnt. It was time for the New Zealanders to come home.

While the activities of J-Force may not have been as intense as the fighting experiences of World War Two, they heralded a new and important role for the RNZAF. No longer was the destruction of the enemy the primary aim. As would be found in succeeding decades, the maintenance of peace would become one of the major roles for the service. It is a function still being carried out today by RNZAF personnel around the world.