Post-War Berlin – City of Unease

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the climax of one of the most remarkable logistic and humanitarian operations in history. Just four years after the defeat of Nazi Germany, Europe was once again in crisis. Germany was divided into two separate countries, West and East Germany. The politically sensitive city of Berlin was also symbolically subdivided. Britain, America and France held portions of West Berlin, while the Soviet Union (Russia) held the Eastern portion and controlled all access in and out of the divided city.

Difficulties arose in the summer of 1948 when Britain tried to introduce a new form of currency to their portion of West Berlin. Soviet leader Josef Stalin used this as an excuse to blockade all land and river routes in and out of the city. This strangle-hold threatened to starve the Allies and the population of West Berlin.

The only way to supply the blockaded city was by air. The Berlin Airlift had begun.

Operation “Plainfare”

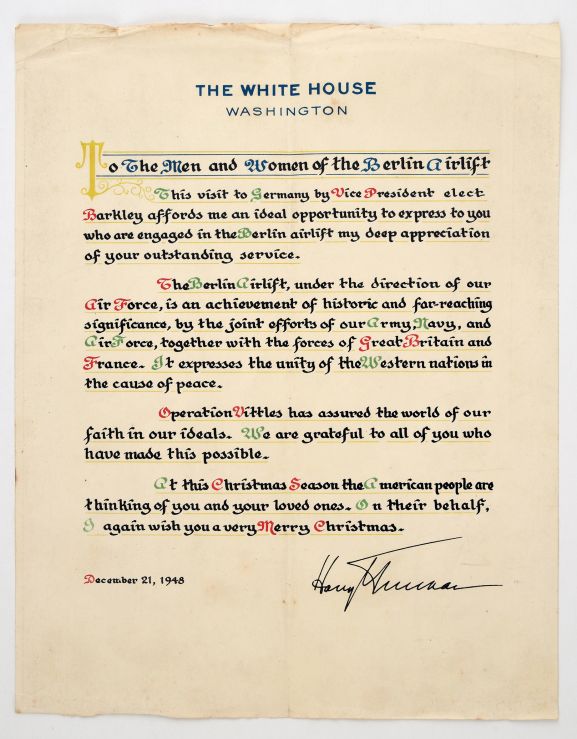

Flights began on 26 June 1948, with the Americans calling the effort Operation “Vittles” and the British Operation “Plainfare”. Operating from bases in the UK and West Germany, the resulting air bridge carried all sorts of supplies, ranging from coal to food, fertiliser to cigarettes. Britain appealed to the Commonwealth air forces for the loan of experienced transport crews to help. Australian crews arrived in September 1948 and were soon joined by their counterparts from New Zealand.

Three crews from No. 41 Squadron RNZAF were selected and dispatched to Europe to assist, later replaced by three more in rotation. They were posted to No. 46 Group of the RAF flying Douglas Dakota aircraft. Other New Zealanders serving with the RAF also flew missions into Berlin with their British squadrons. New Zealander Group Captain Ronald ‘Nugget’ Cohen, happened to be on exchange with the RAF at the time, and was part of the planning staff with No. 46 Group. He has left us with a host of archival material relating to the Airlift in the Museum’s archives.

The RNZAF crews were based at Lübeck on the Baltic. They flew into Gatow airport in the British sector of Berlin in a clockwork train of aircraft that left no room for error. The slightest delay in arrival could mean a return to base with the load. On average, an aircraft landed and left every three minutes. Twelve-hour shifts placed a great strain on the air crew but the effort was worth it. Easter 1949 proved the high point of the Operation with combined crews delivering 13,149 tonnes of supplies on Good Friday alone. Their main load was usually coal, making up nearly half of the total carried by the Kiwi-flown Dakotas.

The Soviets Give In

In May 1949, Stalin realised the blockade had failed and relaxed his grip on Berlin. The Allies continued with the Airlift, however, until September 1949, stockpiling resources in case the crisis restarted. Overall, the Airlift cost around USD $224 million and delivered around 2 million tonnes of supplies and machinery. Undoubtably, the Kiwi crews had made a major contribution, despite their small numbers. The last New Zealanders left Germany in August 1949, and in their year-long deployment transported 622 tonnes of coal and 666 tonnes of other cargo on 473 flights. They brought out considerable mail on the return journeys and over 1,000 passengers (including children suffering from malnutrition). They had also learned a great deal about transport operations. Nugget Cohen later stated that the Airlift taught the New Zealanders ‘more about ground and air control and the possibilities for the carriage of heavy air cargoes in vast quantity than could have otherwise been learned in ten years.’ He was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his role in the command of the operation and Flight Sergeant (later Flight Lieutenant) Edmund Saker was awarded the Air Force Medal for service in Germany.

The Cost of Freedom

There were relatively few losses, considering the huge scale of the Berlin Airlift. In all, the RAF lost five transport aircraft in crashes, with the loss of 18 crew members. The last of these losses occurred on 16 July 1949 at Tegel airport. The Hastings aircraft which crashed after take-off was piloted by 26 year-old Flying Officer Ian Donaldson of Dunedin, a New Zealander serving with the RAF. He had previously served as a pilot on Catalina flying boats with No. 6 Squadron RNZAF in the Pacific during World War Two, and had been Mentioned in Despatches. After the war, like some other Kiwis, he elected to transfer to the RAF. The only New Zealander to die during the Airlift, he is buried at the Berlin 1939-1945 Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery, ironically not far from fellow New Zealanders who died attacking the German capital with Bomber Command just a few years earlier.

Flight Lieutenant Ted Edwards, a New Zealander flying with No. 511 Squadron RAF later reflected on the effect of the Berlin Airlift had on its participants:

‘It was difficult for those engaged in the Airlift, to realise at the time they had won a great victory. There was no dramatic moment at which the aircraft stopped flying and everyone could say “It is over and we have done it.” Airmen and ground crews went home, happy in a job but hardly aware of the importance of their achievement.’

Ted Edwards marked the 50th Anniversary of the Airlift in in 1999, travelling to Berlin with other veterans. The historical significance of their efforts was reinforced when the Mayor of Berlin told the assembled veterans from many countries:

‘If it had not been for the Airlift, there would be no City of Berlin in existence now.’